This is an update to Can you Write Code on an iPad?, in which I tried writing code on an iPad, grew dissatisfied, and then bought a Samsung Chromebook Plus.

Eventually, I also became dissatisfied with the Chromebook Plus, sold it and all my old hardware lying around, bought an iPad Pro, and the cycle of suffering continued. I also tried Windows 10 and the Surface Book 2.

But if you’re here, you probably want to read about about writing code on the Chromebook Plus. Let’s get to it!

Life with a Chromebook Plus

I really liked the Chromebook Plus – at first. It seemed so close to my vision of an ideal computing environment that I thought I’d never use a normal computer again. I bought the device during summer. Every day, I popped the Chromebook in my bike bag and rode to a park along the Willamette River, where I tethered to my phone for an internet connection and wrote code under fresh sunlight.

Doing this was even more magical than it was with an iPad because the Chromebook had a perfectly usable trackpad and ran a desktop version of Chrome. This meant that aside from using Vim over an SSH/Mosh session, which meant some typing latency, I made few compromises to the tools I was already using on my MacBook Pro.

Better yet, the included stylus was the best I had ever used on a tablet at that time. Coming from the iPad Air 2 and several capacitive styli, the Chromebook stylus was accurate and enjoyable to use. This turned out to be the most revelatory part of the experience; more on that later.

Code Locally or Via SSH?

I was so enamored with the setup that I gushed about it to all my friends. Then I began cycling through various configurations to find the best coding experience:

- Developer mode on, Crouton and Ubuntu installed

- Developer mode on, Chromebrew to install coding utilities in the CLI, but no Linux

- Developer mode off, using Chrome apps to edit code

- Developer mode off, using an Android app to run Linux and coding utilities

- Developer mode off, using only SSH/Mosh to a proper Linux server

All of these configurations had their benefits and flaws. Eventually, I settled on using SSH and avoided development mode.

Running Linux via Crouton didn’t work out because I couldn’t get Ubuntu to look or work right on the machine; I don’t know if this was due to the screen resolution or drivers or what, but neither Gnome-based distributions nor Unity worked well on it. Plus, due to the ARM processor, I occasionally ran into packages that wouldn’t compile correctly or just weren’t available. Running Linux on the Chromebook was more of a curiosity than a hard requirement, so after spending some hours on it without success, I moved on. Perhaps GalliumOS would have worked better. I’ll never know.

Chromebrew was interesting as well, but in general I disliked the idea of installing any Linux tools on the machine, or storing code on it. This was because anyone could wipe my entire system just by opening the lid and following the prompts! Installing tons of software locally on the Chromebook also ran counter to my vision for the device, which was essentially a really nice SSH terminal, browser, and tablet.

Briefly, I looked into Chrome apps for writing code, either files stored on the local filesystem, or web IDEs that allowed access to code hosted remotely. None of this… worked very well. Chrome apps appeared to be dead; many hadn’t been updated in years. Google ended up killing the Apps section from the Chrome store later that year, on Windows, Mac, and Linux versions of Chrome. And while you could turn any web application into a dedicated window that allowed full use of the web app’s keyboard shortcuts, promising web IDEs like Eclipse Che just weren’t good enough.

Running Linux in an Android app was pretty awesome, until I A) tried to install some packages that didn’t work and B) hit Control-W to delete a word, which closed the entire app – because there was no way to let an Android app have full control of the keyboard.

So, I settled on using Secure Shell to SSH into a Linux server running on Google Cloud Platform. Secure Shell could establish a SOCKS 5 proxy, and another Chrome app (I forget the name) could route traffic through the proxy, giving me access to remote development servers via Chrome. That worked well!

Android

A two-pound machine that could run a decent SSH client and desktop Chrome would have been cool enough, but what really intrigued me about the Chromebook Plus was Android apps. I switched to the beta channel and began playing with Android apps almost immediately, and doing so turned the device into an exciting hybrid of an Android tablet and tiny development laptop.

It was so cool that when the time came for my wife and I to upgrade our phones last year, I tried an Android phone instead of an iPhone. However, in a surprise twist, the ability to run Android apps was both the most promising and ultimately the most disappointing aspect of the Chromebook Plus!

Promising because using Android apps was often smoother than using Chrome on the machine. I don’t know why this was, but I assume that Android is better optimized for ARM processors than Chrome.

As an example, writing on the included stylus in the web version of Google Keep, or any other web application that provided a drawing surface, was terrible; the line lagged behind my motion to draw it, which made actually writing letters correctly and fluidly impossible. At the same time, the Android version of Keep worked fine. (For drawing, that is. Otherwise, it had odd behavior like always defaulting to the color light blue, occasionally freezing, and so forth.)

However, despite offering better performance, Android apps came with unending difficulties. They were limited to blindingly small fonts, and this could not be changed in the OS’s accessibility settings; when it could be changed after a subsequent update, there was a bug that made the system-wide font setting reset after you quit an Android app. Window placement and sizing was limited. The already odd filesystem management on ChromeOS was even stranger with Android in the mix, where Android apps could not access SD cards in the device!

And let’s talk about those Android apps. Coming from iOS, I thought most of them were garbage. Big services worked well enough – Spotify, Kindle, the NYT app, etc. A couple of apps were even better than their iOS counterparts, like Safari Books Online’s Queue app. However, outside of this small ring of apps, most of them were trash, compared to the iOS ecosystem.

As an example, want to take handwritten notes on Android? Well, for one thing, OneNote wasn’t available on Android on ChromeOS. Because… reasons? Who knows? Google Keep was unreliable (one day it deleted 20 or 30 of my notes, leaving only empty stubs behind). The only app that provided a decent writing experience was Squid, which had no cloud-syncing ability, no iOS or desktop app or any other way to access notes easily.

Meanwhile, apps crashed all the time. I had the visceral sense that Google had no idea how to shove Android into the device, because everything related to Android was unreliable – even after the feature became available on the ‘stable’ channel.

Hardware

Overall build quality on the Chromebook Plus was poor, which I expected. It felt like a nice screen bolted to a crappy keyboard. I didn’t mind the cheap look much, but the case scratched easily. Within weeks, the underside was dinged up.

But if the keyboard was cheap, at least the key travel was sane! Unlike the latest generation of Apple’s keyboards, this felt like you were typing on a keyboard, at least.

And in the area of external connectivity, compared to an iPad, the Chromebook Plus was a dream! The ports were USB-C, which were easy enough to find, and the laptop supported connecting monitors and keyboards.

As a tablet, the device was just too heavy to comfortably hold for long – or even short – periods of time. Generally, I only used it as a laptop or folded over flat as a writing surface. However, its hinge allowed for some positions that were even more comfortable than an iPad, because instead of holding it in your hand, you could prop it up on your lap, chest (lying down on your back), or any stable surface.

Summary

Ultimately, something strange happened after I bought this Chromebook: using the stylus for input quickly became crucial to me. I started writing notes constantly for work, both to plan my code and to maintain context as I was writing it. I also used Android apps to plan and manage my D&D games. The fact that I couldn’t get these Android apps to work reliably so that I could use the stylus – and that web apps couldn’t keep up with the stylus at all – turned into a problem that I didn’t even have before the Chromebook!

In opening up this new aspect of computing, like the possibility of writing notes directly on GitHub pull requests while I did code reviews, and then failing to deliver on the experience, the Chromebook Plus pushed me to find something better.

Did I actually find something better?

Well, I seriously considered a Surface Pro due to the Windows subsystem for Linux, but these reports of light-bleed issues on Surface Pro 2017 models were true! I literally had my money ready to spend on one of these things, and then I walked to my local Microsoft shop and every Surface Pro unit in the store had this ugly light-bleed problem. I’ve never seen that on an iPad or MacBook Pro!

In the end, I sold all my old stuff and bought an iPad Pro, which has a great writing experience. I use that for most tasks involving reading and writing: my work notes, code reviews, daily journaling and plans, running D&D games, reading PDFs, etc.

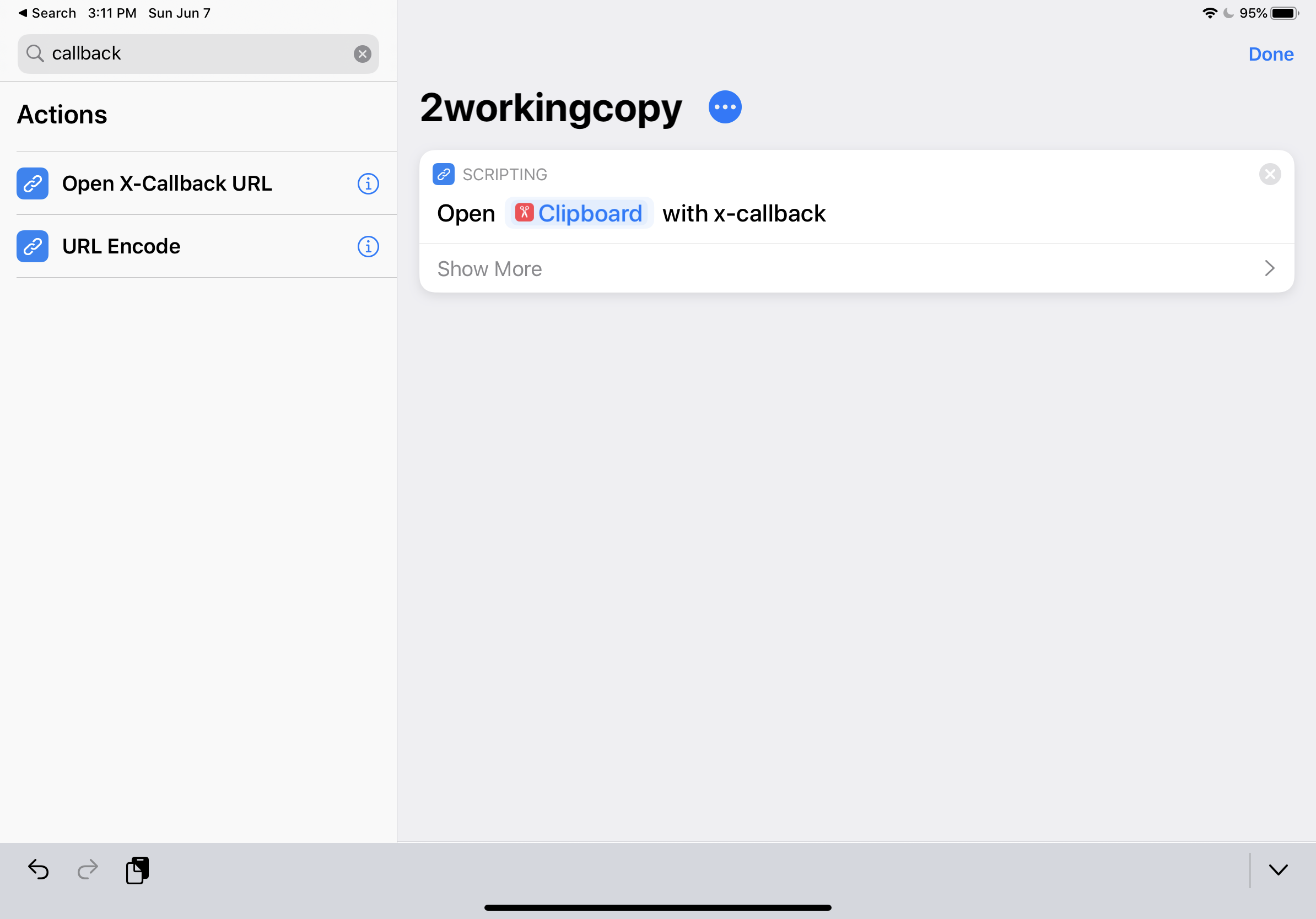

However, even with an iPad Pro and iOS 11, my feelings about coding on an iPad haven’t changed much. In short: Apple can’t even make Command-Tab switch apps without screwing something up (current status: the Command key “sticks” at the software level if you Command-tab too quickly!), and app developers produce absolutely lovely touch-based apps that can’t be controlled with an external keyboard (you can’t scroll up in Slack?!). I use Blink to SSH into a server, or just my MacBook Pro, from the iPad sometimes because I’m keeping the dream alive, but iOS still pales in comparison to using a laptop. Most of the time, I write code, prose, and documentation on a MacBook Pro.

We’ll see what the future holds. I assume that in five years, I’ll be writing, “Can You Write Code in Augmented Reality?” One way or another, my long-term bet is on Apple hardware.