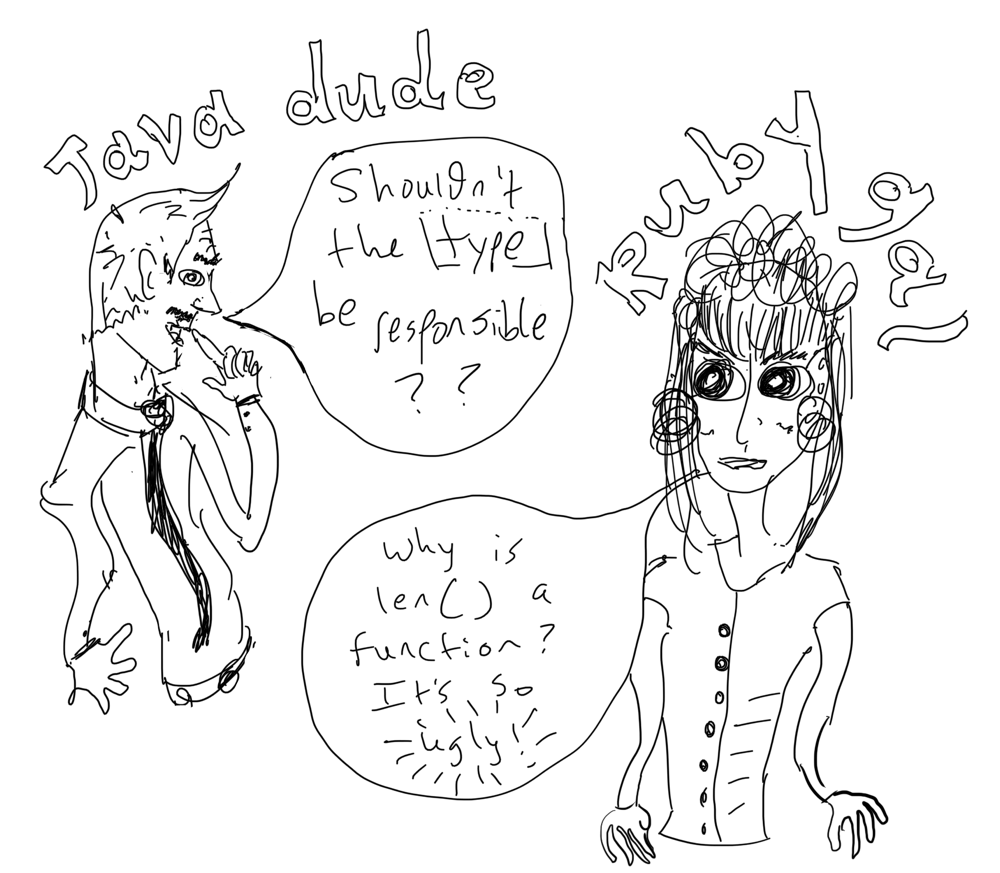

New Python users are often surprised to learn that you call a global function named len() to get the number of items in a container.

For example, if you’re used to a language like Ruby or Java, you might expect a Python list to have a length() method, but no – to get a list’s length, you call len(my_list).

Now, of course, beauty is subjective. But why does Python use this approach instead of giving lists and other containers a length() method?

The short answer is that Guido liked it this way.

The longer answer is that len() makes asking how many items a container has consistent from the surface – len() – down through the implementation, which is done via a special __length__() method.

Let’s take a look at how this works and why it’s better than approaches in Java and Ruby, to use two popular examples.

The Surface

The main reason that len() works so well and has remained part of the Python language is that it provides a consistent surface interface to check the number of things an object contains.

Because len() is part of the language, we know what to expect from its input and output. Whatever “the number of things” means in the context of the object we pass to len(), we know we’ll get an integer result.

That’s all well and good, you might say, but isn’t the object just implementing some kind of length() method that len() calls for us?

In fact, that’s exactly what happens. To work with len(), your class needs to implement a __length__() method.

This simple indirection leads to a deeper consistency: all containers implement the same method to answer this question.

Deep Consistency

Let’s quickly look at how to find the number of items in different container classes in Java and Ruby.

Pop quiz:

- How do you find the number of items in an

Arrayin Java? - How about an

ArrayList? - What about the same questions for an

Arrayin Ruby? - How about the number of characters in a

Stringin Ruby?

And here are the answers:

Array.length()(Java)ArrayList.size()(Java)Array.length,Array.size, orArray.count(Ruby)String.length,String.size, but notString.count(Ruby)

Well, that’s confusing compared with Python, in which len() handles all of these cases.

Java and Ruby both have interfaces and mixins, respectively, that describe objects that have a size or length, but neither approach is as consistent as Python’s. For example, in Ruby, String doesn’t use the Enumerable mixin and thus doesn’t have a count() method like Array.

Or… wait… does it?

irb(main):001:0> x = "hey"

=> "hey"

irb(main):002:0> x.count

Traceback (most recent call last):

3: from /home/andrew/.rbenv/versions/2.5.0/bin/irb:11:in `<main>'

2: from (irb):2

1: from (irb):2:in `count'

ArgumentError (wrong number of arguments (given 0, expected 1+))

So String has a count() method, but it doesn’t do what you might expect, given how count() works with Enumerable objects. Instead of giving us the number of characters in the string, count() takes a string as an argument and counts occurrences of the input string in the target string.

Have I argued the point enough? Languages that use only interfaces or mixins lack the clarity that Python has with len() and __length__().

Protocols

So what does Python do differently?

Ultimately, the difference is the combination of a built-in function, len(), with a consistently-used implementation method, __length__().

There’s even more to the story, though.

The magic method __length__() forms a very simple “protocol.”

A protocol in Python is an informal interface. Practically speaking, it’s a set of methods that begin and end with double-underscores that define some behavior like iteration.

User-defined classes that implement all of the methods of a protocol can hook into system behavior through built-in functions like range() and syntax like for ... in.

I have enough to say about protocols – and especially Python 3.8’s new structural subtyping mechanism – to fill another blog post, so for now I’ll leave it at that.

Check back soon for my next post on Python protocols and protocol classes!