I’ve seen quite a few outages and outage-like scenarios caused by improper handling of network connections over the years. Basic reliability techniques like timeouts, retries, and circuit breakers would have prevented many of these outages – or at least turned them into non-events.

To help drill into your brain (and mine) the effects of using, misusing, and failing to use reliability techniques, I created an outage simulator, ran through a few simulations, and wrote up the results (with graphs). The best part is that you don’t even have to wake up at 2 a.m. to experience these outages!

Table of Contents

- The Outage Simulator

- Upstream Service Outage: API Gateway Only

- Upstream Service Outage: Circuit Breakers, No Timeouts

- Slow Upstream Service: No Timeouts, No Circuit Breakers

- Slow Upstream Service: Only Circuit Breakers

- Slow Upstream Service: 0.5-Second Timeouts Only

- Slow Upstream Service: 5-Second Timeouts Only

- Slow Upstream Service: Retries Only

- Slow Upstream Service: 0.5-Second Timeouts and Retries

- Slow Upstream Service: 0.5-Second Timeouts and Circuit Breakers

- In Summary

- Sources

The Outage Simulator

The outage simulator I created isn’t perfect, but it does let us experiment with combinations of the following:

- Dependency on upstream connections to provide a downstream response (a “homepage” service that requires authentication, recommendations, and popular items)

- A triggering event: either a total outage (the kind that produces immediate socket errors in clients) or a slow upstream response

- Different types of reliability techniques, used in isolation or together, primarily: “API gateways,” timeouts, retries, and “circuit breakers”

You don’t have to use the simulator yourself – feel free to ignore it and study my simulation results.

Upstream Service Outage: API Gateway Only

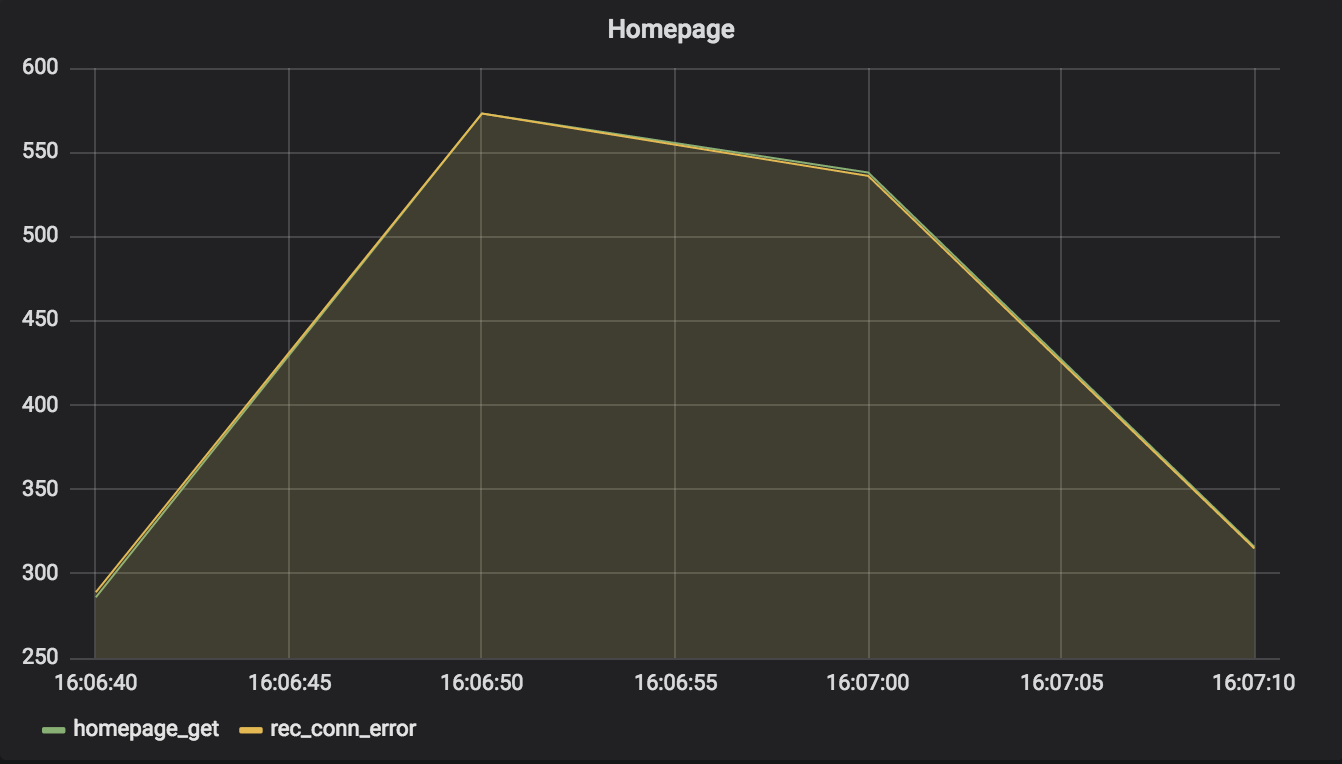

In this simulation, the homepage service encountered immediate socket errors when it requested recommendations from the recommendations service.

Reliability Techniques Used

The only reliability technique used was an “API Gateway.” My take on Nygard’s concept of an API Gateway is a base class that provides common error handling around network requests. The APIClient in the simulator is more complicated than yours might be, because it allows the injection of settings. But at its core, APIClient provides common error handling to the API client sub-classes used throughout the project.

You can see the effect of error handling in the graph. During the outage, the homepage service responded to many requests — about its usual number. It returned an empty list of recommendations, which the hypothetical homepage should skip rendering. Users of the homepage probably did not even notice the difference.

Assessment

-

Using an API Gateway that trapped connection errors allowed the homepage service to gracefully degrade and keep the site responding. Otherwise, the homepage service would have generated user-facing errors.

-

Timeouts wouldn’t have helped because the nature of this simulation is an immediate socket error.

-

Circuit breakers would have stopped the system from continuing to try to connect to the recommendations service, but not improved the number of requests.

Note: In the simulations that follow, this basic level of error-handling provided by APIClient will always be used.

Upstream Service Outage: Circuit Breakers, No Timeouts

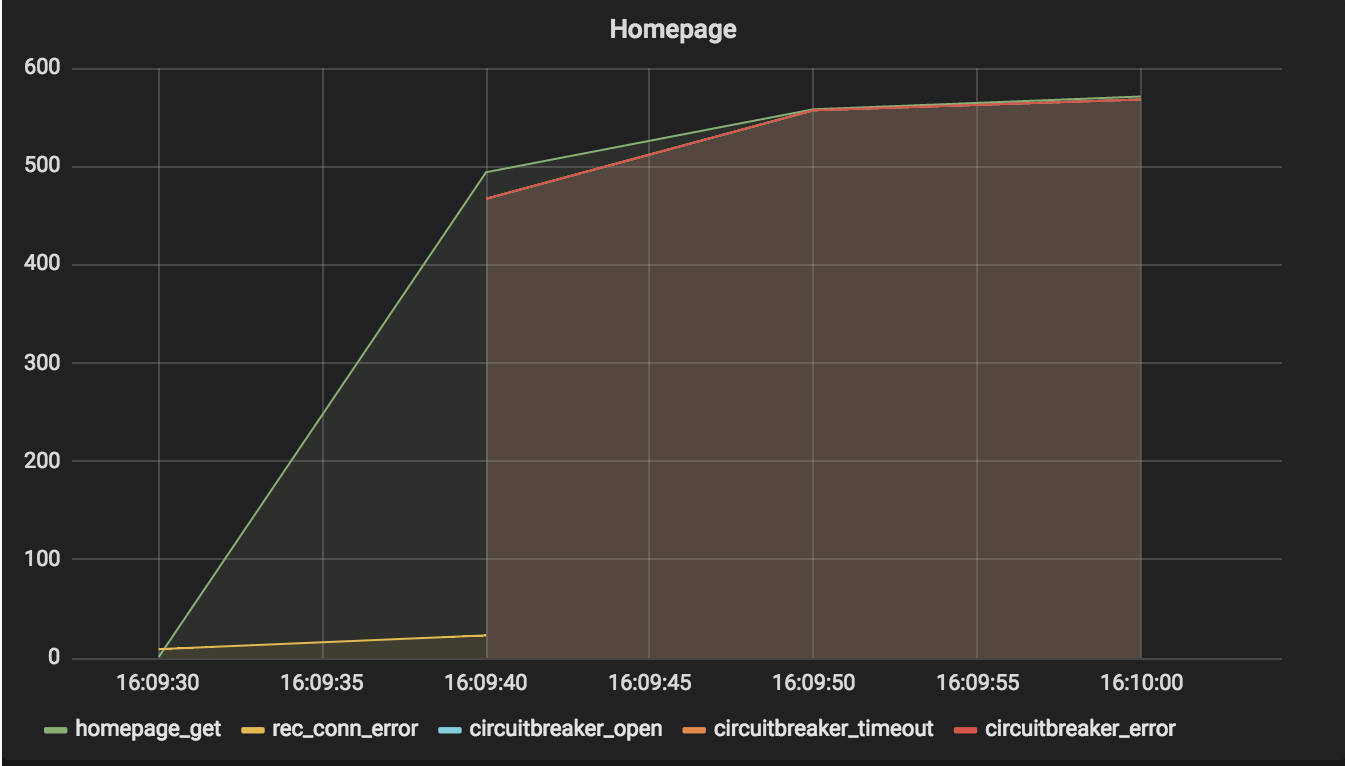

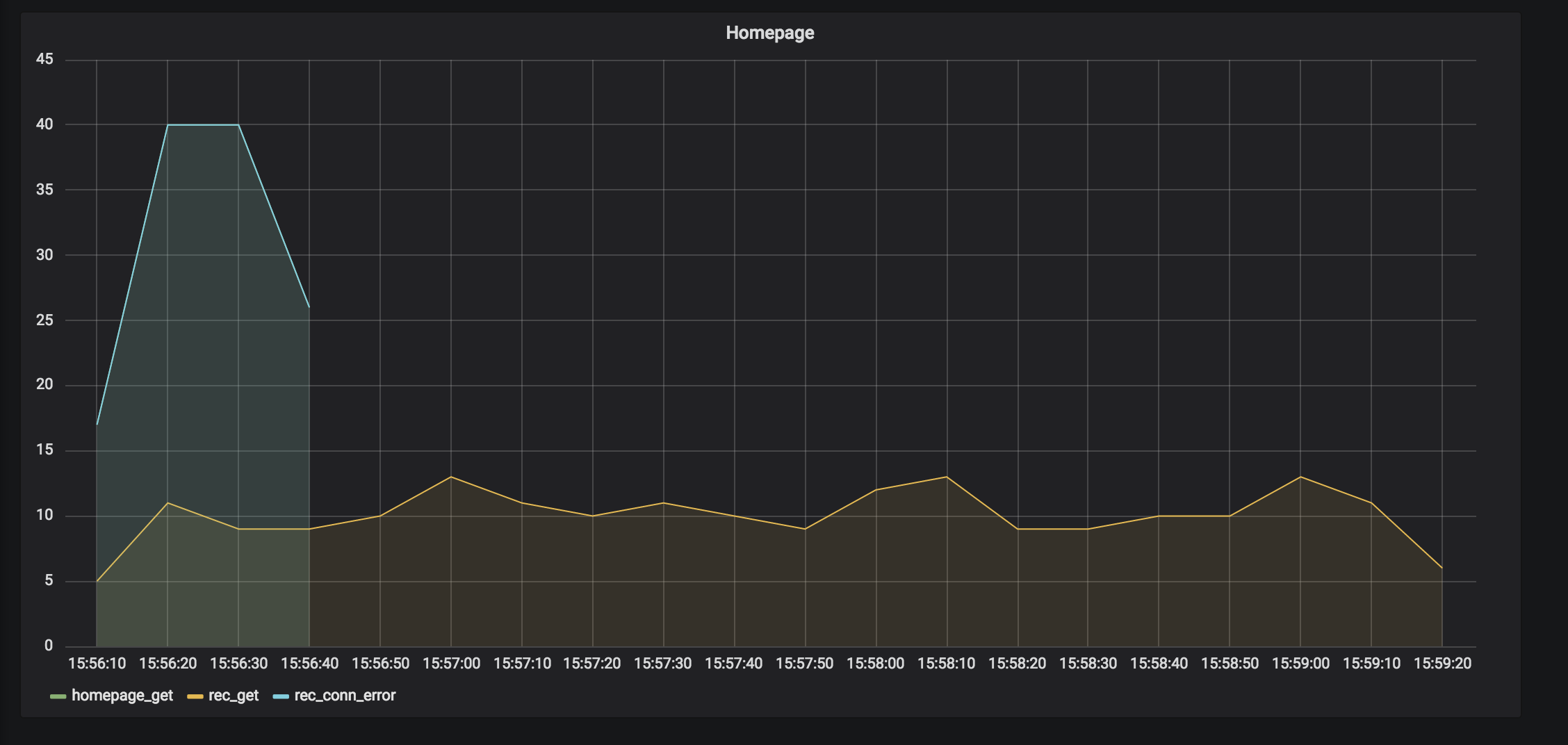

In this simulation, once again, the homepage service encountered immediate socket errors when it requested recommendations from the recommendations service.

Reliability Techniques Used

This time, connections to the recommendations service all used a circuit breaker. After enough socket errors, the breaker opened, preventing further requests.

Assessment

You can see that circuit breakers did not change the result much. This is because the socket error was immediate – so continually requesting recommendations, and thus generating more socket errors, didn’t slow down the homepage service. Circuit breakers provide the most value when failure is expensive, as we will see.

Slow Upstream Service: No Timeouts, No Circuit Breakers

In this simulation, the recommendations service began to respond slower than usual. Attempting to request data from it resulted in variable delays of several seconds.

Reliability Techniques Used

The APIClient class was used, but without any retries or timeouts set. Thus, long requests were allowed to tie up the homepage service indefinitely, resulting in a dramatic drop in the number of requests handled.

Assessment

In my experience, performance problems like this one are the most common source of networking-related outages.

Because there were no timeouts set on the requests to the recommendations, every request hung for multiple seconds. It’s important to note that high timeout values (30 seconds, 60 seconds) would have the same result!

Slow Upstream Service: Only Circuit Breakers

This simulation showed the recommendations service responding slower than usual again. Attempting to request data from it resulted in variable delays of several seconds.

Reliability Techniques Used

Pop quiz: does adding a circuit breaker without a timeout help deal with slow-downs in an upstream service?

If you look at the graph of this simulation, you’ll see that the answer is no! Circuit breakers need something to trip them – they need errors. Slow connections by themselves won’t open most circuit breaker implementations.

Assessment

Once again, every request for recommendations hung for multiple seconds. Circuit breakers alone didn’t help this condition.

Slow Upstream Service: 0.5-Second Timeouts Only

That pesky recommendations service is responding slowly again.

Reliability Techniques Used

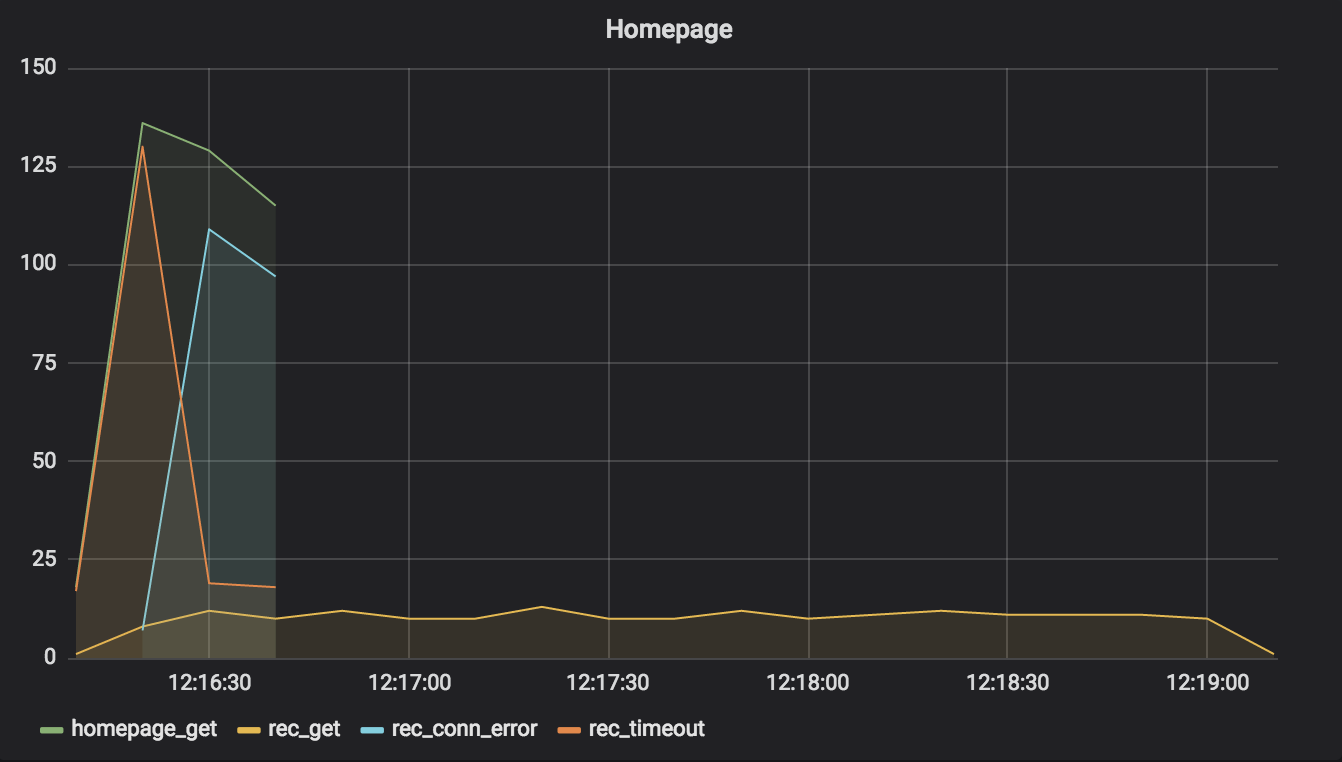

What happens if we only use timeouts? Well, a 0.5-second timeout on all requests makes things a bit more interesting. In theory, this should stop the homepage service from waiting for all requests to the recommendations service that take longer than 0.5 seconds – and you can see in the graph that this happens. Because the homepage service isn’t tied up waiting for recommendations, it handles more requests.

Assessment

There’s something odd about this graph, compared to the others. Did you notice? The timeline is longer. Whereas the other graphs were less than a minute in duration, this one is a full three minutes! What’s up with that?

The answer is important. Requests between 12:16:10 and 12:16:40 represent the 30-second burst of homepage requests made for the simulation. After that, there are no homepage requests on the graph – just recommendations requests.

When clients time out requests, the application servers on the other side usually still fulfill them – eventually. You can see that as a result of just 30 seconds of activity during this performance problem, the recommendations server is busy another 2.5 minutes. That can cause problems during an outage. For example, the recommendations service’s application servers may not auto-restart quickly during a deployment aimed at fixing whatever the problem is, because they’re tied up trying to answer a backlog of reqeusts.

This is why we need circuit breakers. A circuit breaker, once open, won’t send any more requests through. We’ll see what that looks like soon.

Slow Upstream Service: 5-Second Timeouts Only

The sorrowful tale of the recommendations service continues – slow again, blast it!

Reliability Techniques Used

For curiosity’s sake, what do you think happens if we use a higher timeout value? Let’s try a simulation using 5-second timeouts.

Assessment

Using a longer timeout means that the homepage service is tied up longer waiting for recommendations requests. That drops the total answered homepage service requests down quite a bit. In fact, the number is so low, why did we even use timeouts? And this is only a 5-second timeout – I’ve seen people set them as high as 30 seconds as the default!

The longer timeout shifts pressure from the recommendations service up to the homepage service, so the good news for the recommendations service is that it isn’t tied up for multiple minutes after the 30-second simulation burst.

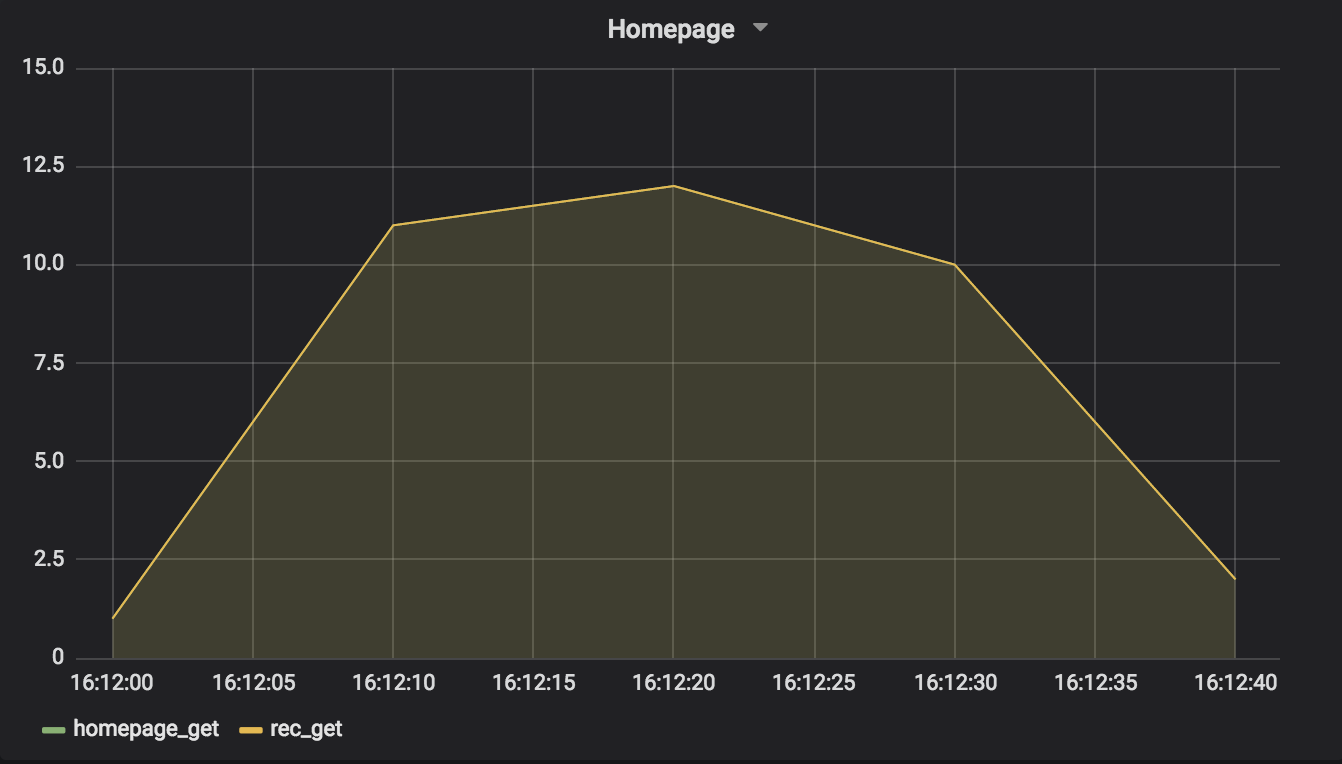

Slow Upstream Service: Retries Only

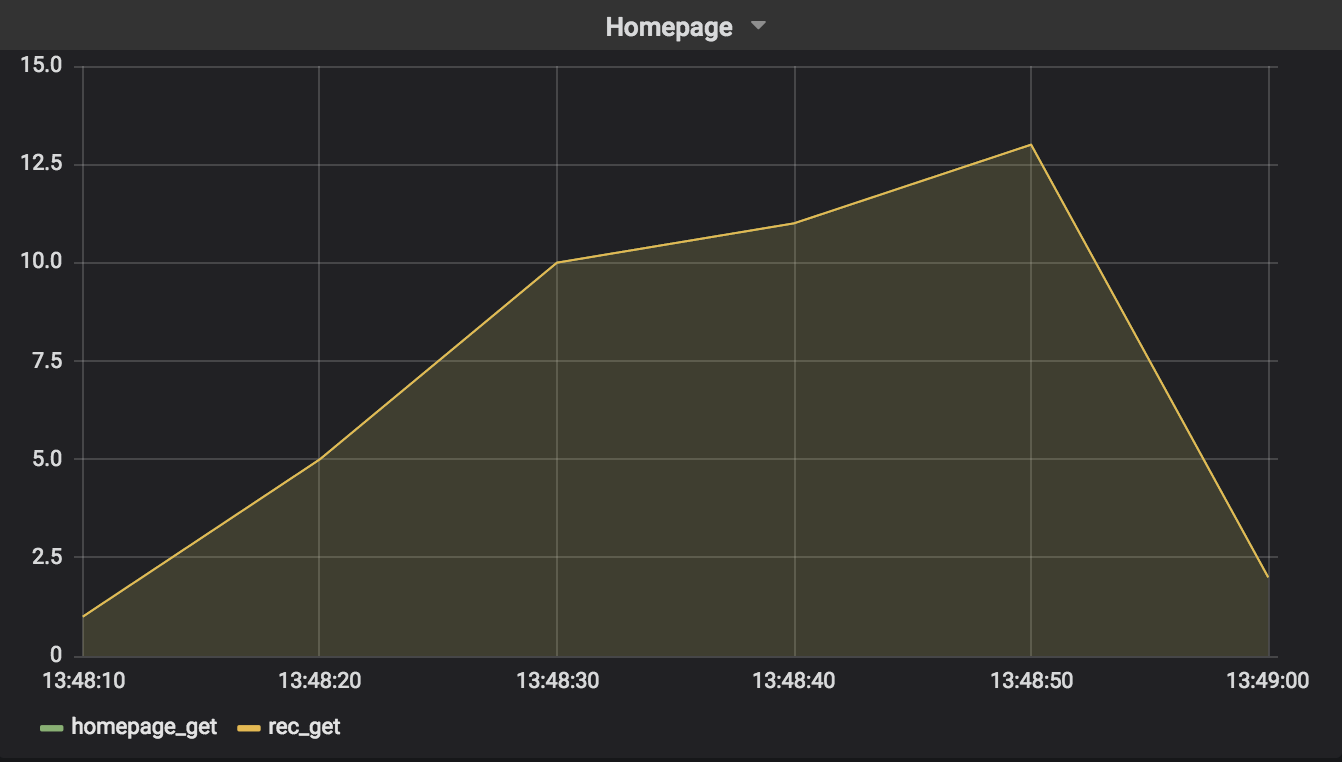

We’ll continue to examine a performance issue with the recommendations service, this time to see what happens when we use retries.

Reliability Techniques Used

‘Retrying’ in this context means that a network client will try again to establish connections that fail, usually a certain number of times. In the outage simulator, if retries are turned on, all API clients will re-attempt timed-out connections three times.

The problem with retries is that they can cause more problems than they solve. Is the upstream service really going to be available in one or two more seconds? Probably not. Also, what happens if all the clients waiting to retry do so at the same time? The upstream service is going to get big spikes in requests.

Exponential backoff is a technique that helps slow down retries as they continue to fail (subsequent retries will sleep longer before trying again). The pinnacle of retrying is combining exponential backoff with “jitter,” as described by an AWS Architecture Blog post. (Jitter is just a cool word for random variation.) Backoff with jitter results in clients retrying at more varied times.

The simulator uses a RetryWithFullJitter class to encapsulate this technique.

Assessment

Despite the fact that retrying with exponential backoff and jitter is better in some respects than simple retrying and retrying with exponential backoff without jitter, you can see from the graph that it still has a deleterious effect. The homepage service manages to reach an average of only 13 requests served. Scream-worthy!

Slow Upstream Service: 0.5-Second Timeouts and Retries

What could improve our handling of this performance issue in the recommendations service? Retries by themselves don’t do it. What if we combine them with timeouts?

Reliability Techniques Used

By now, we’re just combining techniques we’ve already used: retries with a 0.5-second timeout.

Assessment

If you compare the graph in this section with the one in Slow Upstream Service: 0.5-Second Timeouts Only, you’ll see that from the perspective of using retries only, we improved the response time of the homepage service. Unfortunately, from the perspective of using 0.5-second retries only, we made things worse.

The good news is that we can do better!

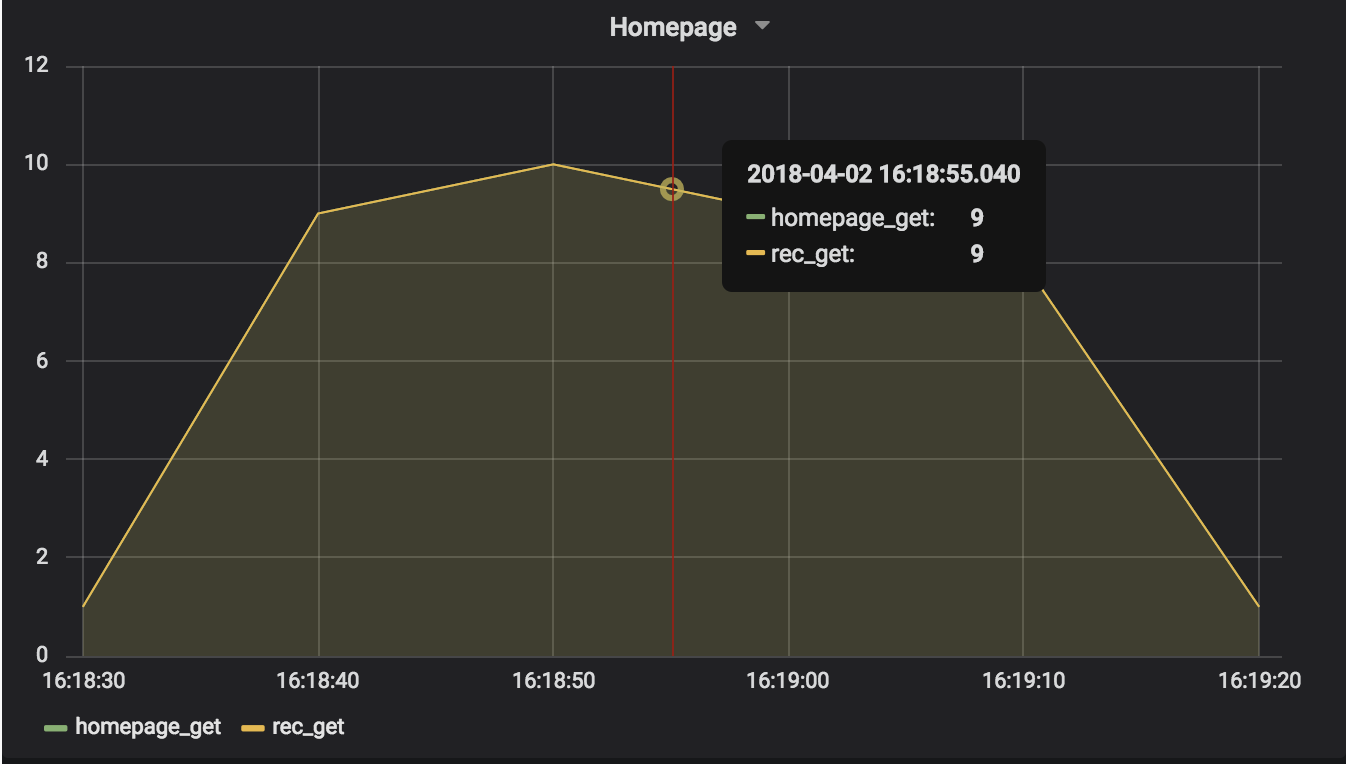

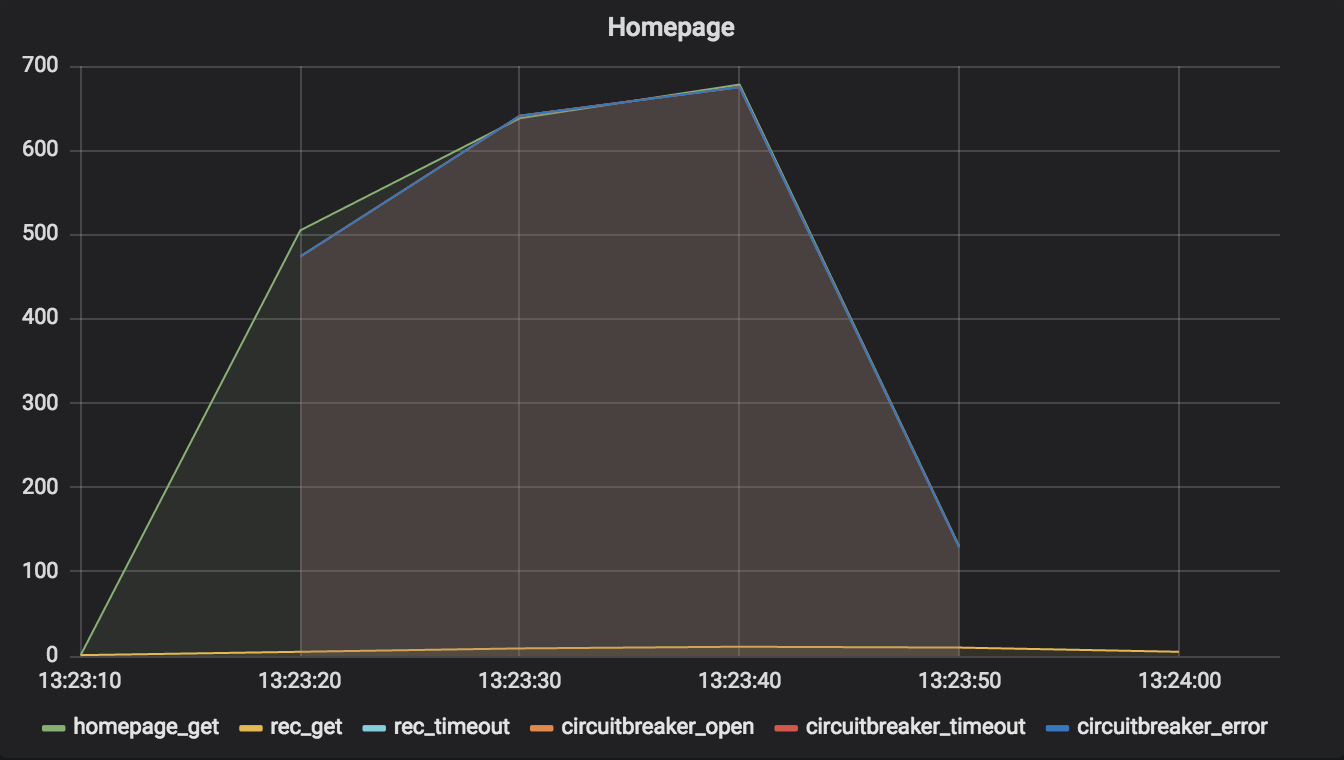

Slow Upstream Service: 0.5-Second Timeouts and Circuit Breakers

If you were wondering whether or not there was a point to all this, if there was any true “reliability” to be found, the answer is yes! Let us proceed to our final simulation of a performance problem with the recommendations service.

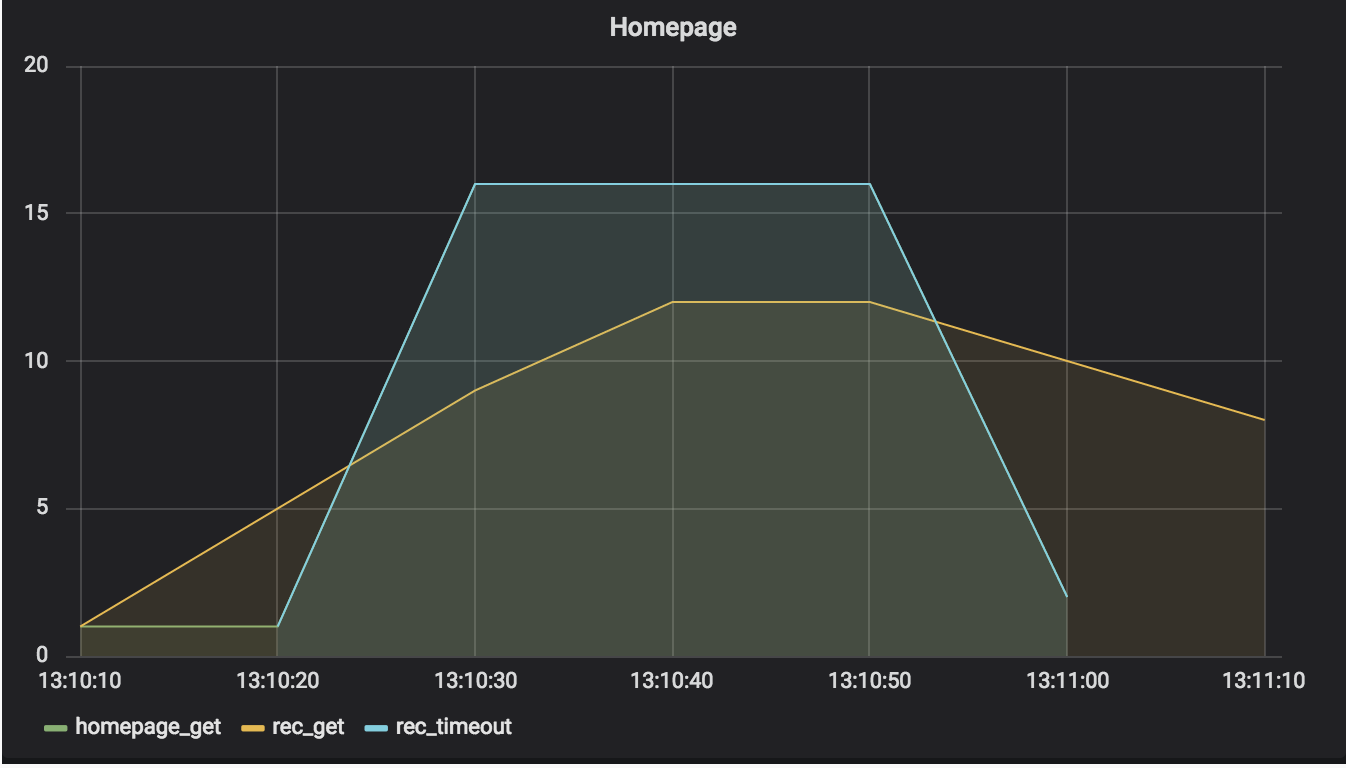

Reliability Techniques Used

This time, the homepage service employed 0.5-second timeouts with circuit breakers around its connections to the recommendations service. To me, this is the gold standard of reliable network connection handling.

Assessment

The graph of this simulation shows why so many people recommend using circuit breakers. Before, when we used 0.5-second timeouts only, we created that long tail of lingering recommendations requests. When we combined circuit breakers with timeouts, we lost the tail – that’s because the circuit breakers opened quickly and stopped the homepage service from making subsequent requests of the recommendations service.

Ah, but there’s more! Surely you noticed how many more requests the homepage service handled in this simulation, compared with the simulation in which we used timeouts only! The numbers were significantly higher. This is again attributable to the circuit breakers. When they opened, the homepage service didn’t need to wait for connections to the recommendation service to time out; they failed immediately, allowing the homepage service’s application server to handle more incoming requests.

In Summary

If you study these simulations, you should have a good sense of why timeouts and circuit breakers work – and why you might want to avoid retries. If nothing else, I hope you internalize that if your application uses network requests, you should probably use the shortest timeout possible and wrap the request in a circuit breaker!

Sources

Many of the techniques discussed in this article are based on Chapter 5, “Stability Patterns,” of the book Release It! by Michael Nygard.

The use of exponential backoff with “full jitter” when doing retries is based on Exponential Backoff And Jitter, published in the AWS Architecture Blog.