In job interviews I try to casually drop that I learned how to program as a teenager writing C code for MUDs1. My intent is to open a fun discussion into why this was awesome. Programming for MUDs taught me the fundamentals of the craft, so I could probably ramble about it for an hour. Just what an interviewer most desires!

But you know what’s messed up? Almost no one seems to have played a MUD or to know what programming for one entails. Interviewers usually ignore the reference. None of my coworkers have ever been former MUD programmers.

I hope to fix this ignorance with some simple background info on MUDs and a few timeless lessons they taught me about programming.

WTF is a MUD

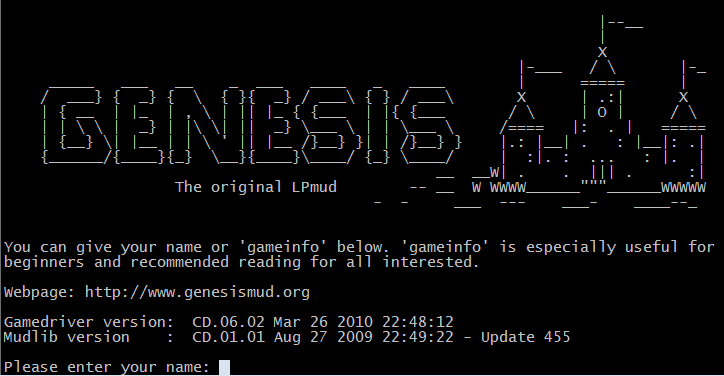

If you don’t know what a MUD is, the acronym stands for Multi-User Dungeon. They are text-based, networked, multi-user games that were most popular in the 1980s and 90s.

</figure>

</figure>

MUDs were on the decline when I started playing them and I suspect even fewer people play them today, the world having largely moved on from text-based games. MudStats reports a peak of 12,000 online users across all games it monitors for the past few days (January of 2014)2. So, I’m not usually surprised when I get a blank look after mentioning the name. But programmers? Who have never heard of MUDs? Unfeasible!

The technical description of a MUD is a networked server built on complex, old and treacherous barrels of C code taped together with razor-wire. The server’s entire purpose is to simulate sword-fighting and spellcasting (usually).

Based on that information alone, it should be obvious that former MUD programming is an excellent humblebrag, whether in casual conversation among peers or in interviews. I hope my post encourages more of this.

The Lessons

1: Listen to your users

The most important thing I learned wasn’t even technical. It was to focus more on what users wanted from the game and less on what I wanted to build. This was a huge, hard lesson and it didn’t sink in until much later.

I spent enormous effort playing around with new ways to do things like simulate damage on more parts of a character’s body. I spent hundreds of hours researching and trying to design new combat and simulation systems, and I never wrote working code for most of these.

Meanwhile, users on the game I programmed for and the people who had decided crazily to ask a teenager to write code for them had lots of small features they wanted to build, only some of which I completed.

2: C is an unholy language that you should avoid professionally unless you are a masochist3

Something happened after I spent a while writing C code for MUDs. I became pretty unhappy. It seemed like the language was designed to kill anyone unworthy of being a programmer. Writing a pointer-dereferencing bug that caused a game to crash in the middle of a tick (a shared in-game moment), dumping players without a save or with corrupted data was an awful feeling.

If you’re new to C, you’re bound to create tons of these kinds of errors as you gear up on the deep magic of ancient codebases written by past wizards and acolytes. I certainly did. After wasting too many nights of my youth hunting through GDB core dumps, I started looking at Java, which was pretty hot back then, with longing. But it didn’t capture me.

Eventually I became a Python programmer and I vowed never to touch a compiled language again4. I broke my vow once to do mobile app development in Objective-C and again to play around with Go. I don’t think Objective-C was as bad as C, and Go was awesome. Perhaps I’ve changed. But I still avoid compiled languages for professional work unless the task requires them.

Update 1/28/2014: The main thing I love about Python, JavaScript and other dynamic languages compared to C and Objective-C is the level of excellence in debugging tools. In my experience tools like ipdb, IPython and the Chrome Developer Tools are superior.

3: Don’t store user data in files

OMG, WTF, I remember so many times when one of my ridiculous pointer errors crashed a game and as a result, someone’s character got jacked-up. This was mainly because characters were saved to and loaded from files on disk.

I’m not faulting ROM or ROT or whatever DikuMUD-derived codebase I used to hack on. I’m sure lots of games write character data to files — this is probably appropriate for tons of use cases. I did not go on to become a game developer, so I can’t speak to how other games handle it. However, I do know that saving user data to files introduced all kinds of problems.

I’m pretty sure ROM did not write all character changes to disk immediately. It saved some things like level advances. That meant that if the game crashed, your character would lose something, usually equipment and experience. Worst of all, if the game crashed in the middle of a file save, the file itself might be corrupted, destroying your character unless there were backups.

Lesson learned. Use a transactional database (also: backups) or something else that can handle doing filesystem writes independent from the main action of the program. Sure, there will still be problems with data loss, and I have no idea how using a transactional database would stack up in a modern MUD. But I’d start there, though, and not with a file.

4: Never make a quick fix

Check out this wisdom on debugging I found in the Merc codebase:

When you find a bug … your first impulse will be to change the code, kill the manifestation of the bug, and declare it fixed. Not so fast! The bug you observe is often just the symptom of a deeper bug. You should keep pursuing the bug, all the way down. You should grok the bug and cherish it in fullness before causing its discorporation.

Seems legit, right? That advice is 20 years old! Written in 1993, it and many other gems can be found in the glorious hackers.txt file left behind like a lost ruin in the codebase of Merc, a MUD engine derived from DikuMUD5. This file was written by badasses.

I don’t remember reading this file or one like it when I was slinging MUD code, but it didn’t matter. Over time, I gained an understanding of the deeper complexities of debugging. Spending quality time in GDB was the natural result of writing C back in the 90s and it probably still is today. But the main thing I learned was not a technology, it was a philosophy: avoid the quick fix.

Every programmer alive knows what the quick fix is. It’s the change you could make that would resolve the surface-level cause of a bug, generally encountered before the root cause. Do you fix the surface issue or go deeper? It’s so tempting to write a quick fix, especially in a game with players losing equipment and experience every time the thing crashes. I wrote many of these and the result was an impenetrable nest of bugs covered in other bugs.

Years later, I still avoid at all costs making a quick fix. Instead, I try to take the time to understand bugs “all the way down.”

Wow, MUDs

To sum up, I learned vastly more than this handful of things while programming for MUDs. The experience taught me all of the fundamentals of programming, from the syntax of my first “real” language (after BASIC, HTML and JavaScript) to maintaining a build system, debugging, my first text editor (PICO!), basic algorithm selection and more.

I checked out some CircleMUD code6 while writing this post just to freshen up on how it worked, since I had not read any MUD code in probably a decade. I couldn’t find any ROM or ROT code, but it didn’t matter — CircleMUD shared enough of the same DNA. It was like picking up an old family album covered in dust. Good times.

I could probably mine the topic for 10,000 words more words, but for now I’ll stop here. We all have our first experiences with code. They’re unique and special snowflakes. MUDs were mine.

- I'm not interviewing or looking right now, just FYI. ↩

- http://mudstats.com/ ↩

- I'm being dramatic. If someone said the same thing about Python I would write a tract against them. I'm open to using the right tool for the job, even if that turns out to be C. In fact I'm interested in finding a reason to write C again, maybe a Python extension. ↩

- I am using "vow" in the most hyperbolic way possible. I was a teenager when I developed my initial feelings about compiled languages. I am now an adult and have worked with compiled languages and even developed a strong fondness for one — Go. ↩

- http://pastebin.com/BHupYEAJ ↩

- Unofficial GitHub mirror: https://github.com/bgess/CircleMUD ↩